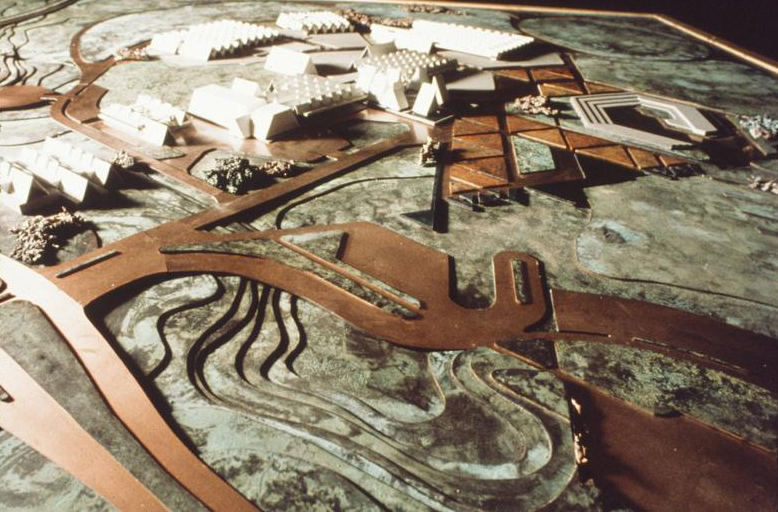

Sprawling over 19.5 hectares and boasting a series of triangular buildings with exquisite detailing, the International fair grounds of Dakar, known as the CICES (Centre International du Commerce Extérieur du Sénégal), counts among the most iconic examples of 20th century architectural heritage on the African continent. The complex was commissioned by the first president of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor, a poet-politician who sought a novel, universal African architectural language shed from Western referents.

![]()

CICES was part of a wider cultural and political agenda by President Senghor to promote Panafricanism and a sense of global citizenship for the Senegalese population, most notably through the First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966). Senegal represented an important node in a wider network of Panafrican cultural gatherings in the postindependence era, including the first Pan-African Cultural Festival (PANAF) (Algiers, 1969), and the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, (FESTAC) (Lagos, 1977).9

![]()

Senghor launched an international competition in 1969, and stated in the brief that he was seeking to create a fair located in the outskirts of Dakar that would house the FIDAK (Foire Internationale de Dakar), a biennale event that would be the ultimate economic and cultural forum for Africa. Senghor’s ambition for a Pan-African complex extended to its architectural style, which he hoped would reference the African vernacular more widely, while embodying a progressive spirit towards the future. Young French architects Jean-François Lamoureux and Jean-Louis Marin won the competition with a design that captivated Senghor– psychedelic triangular buildings, which the president saw as a direct reference to one of the pinnacles of African civilization: the Egyptian Pyramids. Senghor’s vision capitalized on the confluence of exhibitors from all over Africa (and beyond) during the FIDAK. The FIDAK would become a start-up incubator, offering support facilities to foster innovation, with the aim of spurring economic growth and collaboration.

![]()

CICES was part of a wider cultural and political agenda by President Senghor to promote Panafricanism and a sense of global citizenship for the Senegalese population, most notably through the First World Festival of Negro Arts (1966). Senegal represented an important node in a wider network of Panafrican cultural gatherings in the postindependence era, including the first Pan-African Cultural Festival (PANAF) (Algiers, 1969), and the Second World Festival of Black Arts and Culture, (FESTAC) (Lagos, 1977).9

Senghor launched an international competition in 1969, and stated in the brief that he was seeking to create a fair located in the outskirts of Dakar that would house the FIDAK (Foire Internationale de Dakar), a biennale event that would be the ultimate economic and cultural forum for Africa. Senghor’s ambition for a Pan-African complex extended to its architectural style, which he hoped would reference the African vernacular more widely, while embodying a progressive spirit towards the future. Young French architects Jean-François Lamoureux and Jean-Louis Marin won the competition with a design that captivated Senghor– psychedelic triangular buildings, which the president saw as a direct reference to one of the pinnacles of African civilization: the Egyptian Pyramids. Senghor’s vision capitalized on the confluence of exhibitors from all over Africa (and beyond) during the FIDAK. The FIDAK would become a start-up incubator, offering support facilities to foster innovation, with the aim of spurring economic growth and collaboration.

Lamoureux and Marin had just completed one year of civil service in Senegal after graduating from architecture school in Paris, and decided to participate in the competition upon their return to Paris. They returned to Senegal in the autumn of 1971 and completed their design of the competition on the kitchen table of Lamoureux’s mother’s home. The architects understood that they wanted their proposal to celebrate and pay homage to African visual culture, and this would separate them from the other competition proposals.

Lamoureux and Marin had just completed one year of civil service in Senegal after graduating from architecture school in Paris, and decided to participate in the competition upon their return to Paris. They returned to Senegal in the autumn of 1971 and completed their design of the competition on the kitchen table of Lamoureux’s mother’s home. The architects understood that they wanted their proposal to celebrate and pay homage to African visual culture, and this would separate them from the other competition proposals.Lamoureux and Marin’s design for the Complex employs Modernist principles in its circulation and layout, while simultaneously using vernacular aesthetic and organizational principles–triangles, traditional Senegalese village planning, and passive design appropriate to the context.

The result is a complex that largely uses triangle motifs and a combination of concrete and vernacular materials to offer a multitude of rich spatial experiences. CICES offers a unique example of post-independence African Modernism, working to craft a new national identity and narrative for Senegal. These concepts were implemented with the knowledge and skill of local craftspeople –a prime example of this is the manually installed facades of the seven regional pavilions, which were designed and prototyped through a collaboration between artisans from each of the seven regions in Senegal and the architects.

Built and continuously owned by the Ministry of Commerce of Senegal, CICES has undergone several changes that have altered its overall original design, chiefly: the encroachment of a dense residential neighborhood (now known as CICES Foire) within its original property line (built on ‘voids’ in the design such as parking and service areas). Although CICES Foire’s emergence destroyed much of the CICES grounds, the neighborhood is vibrant and active and its residents are important stakeholders in the future of the site. The addition of new buildings (permanent and temporary) on CICES property, as well as uncoordinated maintenance and rehabilitation efforts, have compromised the heritage value of the complex (such as changes to the auditorium roof and decorative dropped ceiling). Despite these changes, CICES still retains its architectural integrity and emotive power; the buildings maintain a high likeness to their original condition, sophisticated detailing is still in place, and original furniture and appliances remain present throughout.

CICES has not yet been officially recognized as historical heritage in Dakar, despite the iconic status it holds amongst all fringes of the Senegalese population. Only 8% of heritage sites in Dakar were built after 1960 (the year of Senegalese independence), with many of those on the registry not holding the same cultural prominence as the CICES complex. Colonial buildings account for at least 85% of the heritage registry in the Dakar region, and natural sites account for another 6%. Many of the pre-1960 Dakar heritage sites are former bastions of French Colonialism or the resulting slave trade. There are very few post-independence Modern buildings which have been preserved to commemorate Senegal’s independence and corresponding architectural innovation—and those included in the registry represent branches of government or large institutions (such as the National Assembly building, erected in 1960).

CICES’ greatest strength has been its continuous use and the iconography of the site amongst the residents of Dakar. In the quickly-densifying city of Dakar, CICES offers a free and open landscape for leisure–a critical reprieve from the bustling city. The pathways on the site are used by joggers and walkers from the surrounding neighborhood to host evening classes in the open spaces adjacent to the auditorium, administration building, and in the mango grove. CICES continues to be a cultural and commercial destination for Dakarians and international visitors attending the Fairs. Yet, CICES’ popularity has been diminished by the construction of a new convention center developed in the neighborhood of Diamniadio on the outskirts of Dakar, which also has a Radisson hotel. The new state-of-the-art center opened its doors in 2014, and since, CICES has hosted less prestigious events.

![]()

To be able to survive, CICES is obliged to rent its exhibition halls for rice storage, and its technical pavilion to a printing house and storage companies. Many of the cultural facilities on the site are no longer operational due to a change in program or a lack of maintenance and operational capacity. For example, the regional pavilions, originally designed as galleries to showcase craft and art from the seven regions of Senegal, are rented out to private businesses for income generation. The cinema at the base of the regional pavilions has been shuttered (although the project team recently revived the cinema for a pop-up screening). The inherent potentials of CICES for the city of Dakar and its vibrant cultural scene are striking.

![]()

Since 2021 Aziza Chaouni Projects and Mourtada Gueye Architects have been working together to push for the conservation and adaptive reuse of the CICES complex, with the support of the Getty Conservation Institute. Our work has included building an archival history of the site, collecting oral testimonies of public and private stakeholders, a full physical diagnosis and architectural survey of the site, the completion of a Conservation Management Plan (CMP), student workshops, an academic colloquium, and various community engagement activities - including a short film festival in the CICES cinema (previously defunct).

The site currently awaits the implementation of the Conservation Management Plan, which was developed in cooperation with site operators, the CICES Foire neighborhood, Dakar’s creative community, civil service representatives, and many others.

![]()

To be able to survive, CICES is obliged to rent its exhibition halls for rice storage, and its technical pavilion to a printing house and storage companies. Many of the cultural facilities on the site are no longer operational due to a change in program or a lack of maintenance and operational capacity. For example, the regional pavilions, originally designed as galleries to showcase craft and art from the seven regions of Senegal, are rented out to private businesses for income generation. The cinema at the base of the regional pavilions has been shuttered (although the project team recently revived the cinema for a pop-up screening). The inherent potentials of CICES for the city of Dakar and its vibrant cultural scene are striking.

Since 2021 Aziza Chaouni Projects and Mourtada Gueye Architects have been working together to push for the conservation and adaptive reuse of the CICES complex, with the support of the Getty Conservation Institute. Our work has included building an archival history of the site, collecting oral testimonies of public and private stakeholders, a full physical diagnosis and architectural survey of the site, the completion of a Conservation Management Plan (CMP), student workshops, an academic colloquium, and various community engagement activities - including a short film festival in the CICES cinema (previously defunct).

The site currently awaits the implementation of the Conservation Management Plan, which was developed in cooperation with site operators, the CICES Foire neighborhood, Dakar’s creative community, civil service representatives, and many others.

9. Murphy, David. “Performing Global African Culture and Citizenship: Major Pan-African Cultural Festivals from Dakar 1966 to FESTAC 1977.” Tate Papers, 2018. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/30/performing-global-african-culture-and-citizenship.